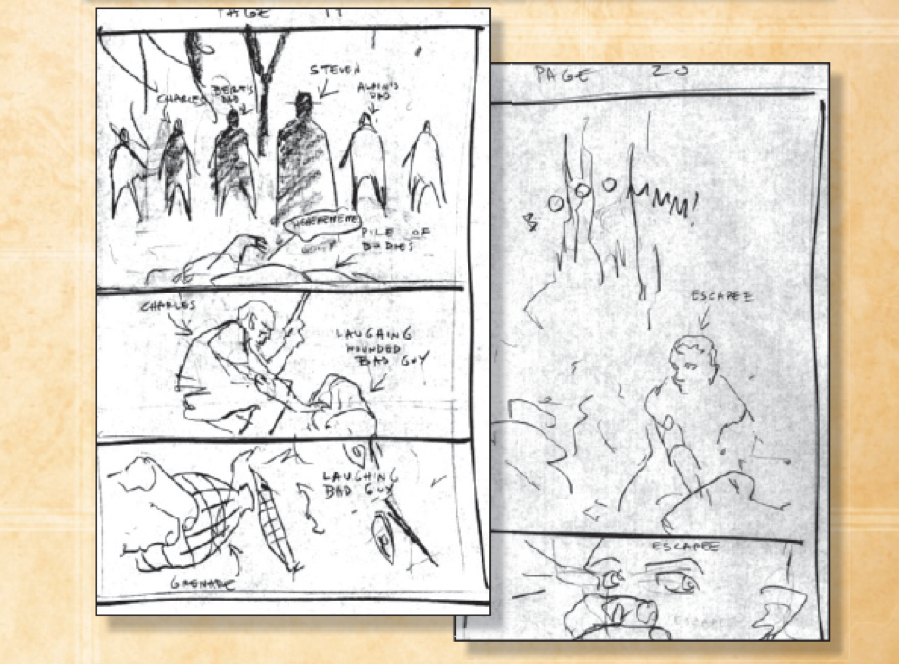

Treachery #1 Sketchbook: Jae Lee’s page layouts with story notes

A few months ago, I gave a talk to the University of Winchester’s Comic Book Society about the world of writing comics. Most of the people there were aspiring writers and several were both writers and artists. All wanted to break into comics. As part of my presentation, I shared a Q&A I had completed several months previously for another student who was interested in creating illustrated books. The Comic Book Society found the piece both helpful and informative, so I thought I’d share it here. If you’ve ever wondered about how comics are created, both for indie publishers and for large mainstream companies like Marvel, read on!

Q&A: Creating Comics

- What would you consider the first piece graphic fiction that you wrote? When did you write it?

Some of my earliest memories are of writing stories and drawing pictures to go along with them. When I was very young I wanted to be both a writer and an artist, but while I was praised for my writing, I was discouraged from drawing. My school was both conservative and old-fashioned, and the generally accepted opinion was that university-track students should focus on traditional academic subjects and leave art alone. (Crazy, I know.)

In my teens I gave up drawing seriously. I continued to write but I kept most of my work secret. Looking back, I realize that right through high school I led a kind of double life. I was keenly aware that the worlds I wanted to write about were deeply disapproved of. I loved supernatural fiction, fantasy, sci-fi, and all sorts of speculative fiction, but the only type of work that received public approval was realistic, and that meant prose without pictures.

Although I still read some comics, I didn’t dive whole-heartedly into graphic fiction again until I found out that Stephen King’s Dark Tower series was going to be transformed into graphic novels. At first I was hired as a Consultant on the project, and then I was hired as one of the co-writers. At that point I immersed myself in graphic fiction and it felt like I’d reopened the door to a world I loved.

So, to return to your original question . . .

I have a very visual imagination, and so whenever I write a story I have specific images in mind. When I began plotting the Dark Tower graphic novels, this relationship between words, images, and the story’s sequence of events became more formalized.

- Do you ever contribute graphics to a novel as well as text?

I don’t contribute graphics, but as the person in charge of plotting the story, I often act as the “director” of each page’s visuals. (There are definitely exceptions to this, and I will discuss them in my answer to question 4.) When I am responsible for the story beats, or the visual progression of the action, I break down each story into pages, and each page into panels. Every panel contains description and commentary, and (if I am also scripting) dialogue and captions. With all of these, I try to convey not just action and style but mood. When the artist and I get into the swing of the story and he or she understands the world I’m creating, it works really well.

- Are there any artists you prefer to work with? Why?

Over the years I have worked with well over a dozen different artists and I have enjoyed all of these experiences. Each artist is different, and what he or she brings to the project is unique and powerful. The resulting work is a full collaboration–each person contributing their skills to create something that neither would have actualized on their own.

When a comic book writer is also an artist, the resulting work is the fulfilment of one person’s imaginative vision, and I have always wished that I could create this kind of graphic fiction. However, when two or more people work together to create a comic, the result is also magical. I love the moment when I receive the first pencilled pages of a graphic story. It feels like the characters have stepped out of my mind and onto the page.

- Is there a typical process in the creative production of graphic novels? Would the text usually be produced before the art?

When a single person creates both the text and the art, that writer/artist has complete control over the story. Some writer/artists begin with an image; others begin with a story idea or a phrase. However, when an artist and writer work together, it is usually the story that comes first. That being said, the balance between art and story can vary. For example, a writer might see an artist’s work and be inspired by it. In that case, the art comes first.

If a writer and artist have formed an ongoing collaboration, they often create new story ideas by brainstorming. If the writer brings the germ of the idea to the artist, the artist will start to do sketches, building faces and bodies for the newly created characters. He/she will also begin to sketch the landscape, giving the comic its feel. In this kind of collaboration, the story and the art grow together in a very organic fashion.

Another way to create a comic is for the writer to finish the full script, including dialogue and captions. This full script then goes to the artist who beings character sketches. Once the artist and writer find the “look” they want for their characters and their landscapes, the artist will then begin the pencils. These pencilled pages function like rough drafts. Any corrections are made, the drawings are finalized, and then the pencilled pages are inked. Often, lettering is added to the inked pages, and color is added last of all.

An incredibly important part of this process is the editor. Some writer/artist duos create their work on their own and submit final manuscripts to publishers. However, very frequently story ideas are pitched to publishers early on in the process, when there is an outline, if not a full script, as well as character sketches and one or two sample art pages. The editor who accepts the project will then be an active member of this artistic collaboration, offering feedback on both the story and the art.

Yet a third method for creating comics is “the Marvel Method” or the plot script, as opposed to the full script. (Interestingly, Marvel is using this method less these days, while I believe that DC is using it more.) As you’ve probably guessed, this method is frequently used in superhero comics, and it moves the responsibility for story structure and story pacing from the writer to the artist. For this method to succeed, the artist also has to have great sequential storytelling skills, since he or she is doing the bulk of the moment-to-moment visual narration.

The Marvel method is very fluid. At one extreme, the writer begins by writing a very loose outline. This outline is then given to the artist who spins the story into a visual tale, sending a more-or-less complete visual story to the writer, who then adds in captions and dialogue. In my experience, there is usually a lot more back-and-forth between the artist and writer(s), making the work more collaborative.

I’ve worked in the Marvel style many times. Here are my experiences:

When we began the Dark Tower comics back in 2005, I worked with the spectacular artist Jae Lee, who was an accomplished storyteller in his own right. I learned a tremendous amount from him. The Gunslinger Born (our first graphic novel) was created in the Marvel style, or plot script, which meant that Jae was in charge of breaking the story into panels and pages. However, as the person responsible for plot, I was responsible for adapting Stephen King’s 600+ page novel into a visual story consisting of seven issues. (Originally Marvel wanted the story to be told in six issues, but six issues just didn’t provide enough room to do justice to the tale.) I also knew that these six issues would eventually be gathered into a single book and would be renamed chapters. At that point, The Gunslinger Born would be physically transformed from a series of comics into a graphic novel.

I wrote The Gunslinger Born as a single tale (called a story arc) broken into individual scenes, each of which centered around specific action and character interaction. Taken together, these scenes told a larger tale. (Imagine describing a film, scene-by-scene, where the characters’ internal states have to become physically manifest on the screen.) As stated earlier, I was not responsible for breaking the story down into panels and pages, but I was responsible for breaking it down into issues. That meant my arc had to be broken into seven sections or chapters, each of which contained ample action, so that Jae could create something fantastic, without crowding or cramming in too much. (Jae was limited to about twenty-two pages of art per issue.) To make matters more complicated, the first six of these chapters had to have cliffhanger endings, so that fans would keep reading. The seventh and final issue had to have a satisfying ending, even though I knew that the story would have several sequels.

Breaking a story into segments can be tricky, since each segment has to function as a whole, and so has to have a sense of forward momentum and balance. In comics, especially adventure comics, it’s considered bad form to have an entire issue spent on a single conversation between two static characters, no matter how interesting that conversation might be. Whenever long conversations were necessary, I tried to give Jae something more dynamic to work with, such as a flashback or an image illustrating the subject of the conversation.

Once finished, this outline went to the editor. (The Dark Tower editors were fantastic and taught me a lot about comics.) Once I made any corrections/changes that the editor suggested, the outline went to Jae Lee.

Using my outline, Jae broke my seven segments down even further, creating twenty-two to twenty-four individual pages (depending on our allowance), each of which contained anywhere from a single splash image to about eight panels. (In present day mainstream comics, six panels is considered the upper limit, with a preference for five.) Jae liked to use a rhythm of about six panels per page, but he would break these up with stunning splash pages or really interesting panel combinations.

Once Jae’s pencils were complete, they went to Richard Isanove for inking and for color. (Together, Jae and Richard created magic.) At the same time, the finished pencils and plot went to Peter David, who would take my outline and Jae’s art and write the dialogue and captions that would appear on the page. Scripting comics this way is an incredibly difficult job, and Peter’s finesse was amazing.

After the end of The Battle of Jericho Hill, the Dark Tower team worked with a different version of the plot method, one more like the writer/artist sample discussed earlier. In these later Dark Tower graphic novels, I was responsible for breaking the story arc into issues, pages, and panels. The artist would then draw the images I described. Once again, the finished pencils would go to the colorist and scripter, and then finally, to the letterist. (As you can see, the Marvel style is more like a production line, since everyone involved has a very particular job.)

- Which people and what number of people are involved in the production of a graphic novel? How is each of them involved?

As you can see from my previous answers, the number of people involved in the creation of a graphic novel varies tremendously. The smallest number is one. That is when the artist/writer is also the editor and publisher. This happens a lot in web comics and in self-published comics. The next number is two: the artist/writer (one person) and his or her editor. This happens a lot in small press or literary comics. After that, the numbers begin to rise. At Marvel and DC, there are often two writers, two artists, a letterer, and sometimes two editors.

- Do you collaborate closely with the person contributing the graphics? How is it necessary for people in different roles to collaborate in the industry you work in?

At big companies like Marvel, company policy is to have all work–both story and art–go through the editors. (This won’t apply to previously established artist/writer teams, but will apply to artists and writers paired by the company.) Often this means that the artist and writer don’t collaborate directly. I think this came about for numerous reasons, one of which (sadly) is to try to head off any conflicts between writers and artists. It also means that the company has more control over the product that is produced.

However, I whole-heartedly believe that a comic works best when the artists and writers are allowed to work closely together. This is an amazing experience and not only creates wonderful comics but fosters camaraderie and friendship. Luckily, even when all art and writing is required to go through the editors first, individual editors are often very open to having three-way discussions.

- Who comes up with the idea for a novel and how is this initiated? What role might this person/people typically play in the production of the novel?

Usually the idea originates with the writer, or with a writer and artist who function as a partnership. There are lots of these partnerships going in comics. Once an idea has been fleshed out, it becomes a pitch, and these pitches are sent to comic book companies and publishers.

If the pitch is for an established character owned by a comic book company (such as Marvel’s Spiderman or DC’s Superman), writers spin pitches and send these story ideas off to an appropriate editor. For example, if I had an idea for a Spiderman comic, I’d send a pitch to one of the editors in the Spiderman office at Marvel. In this kind of pitch, the writer has to know about the character’s history and personality as well as the character’s fan base. For example, a story about Spiderman participating in the Great British Bake-off just wouldn’t sell!

As I said earlier, sometimes writers and artists form partnerships and they submit pitches together. Submitting art with a pitch is especially helpful, since comics and graphic novels are a visual medium, and the artist’s work gives the editor a sense of what the comic will look like.

If the pitch is accepted, then the comic will move into production. (If a writer submits a pitch and it is accepted, but he/she doesn’t have an artist to work with, one of the company’s in-house artists will create the visuals, or the company will reach out to an artist whose work fits with the story idea.) Many writers say that they pitch ten ideas for every story taken. Luckily, once a writer is established, the pitch can be much looser and informal, since the quality of his/her work has already been established.

On the more artistic and indie end of graphic fiction, a writer/artist, or a writer and artist pair, also submit pitches to publishers. Often these pitches are for books that have already been written, or for a story that is in the works already. As with mainstream comics, it is really helpful (and perhaps even necessary) to submit sample art as part of the pitch. In indie and artistic/literary graphic fiction, the story ideas also originate with the writer or the writer/artist pair.

- Do you write for different audiences? To what extent might it be necessary for you, or the people responsible for researching the audience, to research them?

I believe it is most important to write from the heart. If you like a character that is an established figure for Marvel and DC and you’ve already read a lot of their comics, then go for the pitch! You are part of that audience already.

In terms of indie comics and artistic comics, write for yourself and write what you love. The question of audience will probably come later, when you try to sell it. However, it is probably important to keep in mind whether you are writing for children or for adults, since a children’s book probably won’t be published if it contains very adult themes. (I have read some really great picture books for adults, so every statement has a qualification!)

Another thing to keep in mind is that these days, publishers often have very specific requirements for picture books, children’s chapter books with illustrations, and even comics. So, it is probably good to have a general idea of what these different terms mean to publishers.

- Can you give an example of how your work might differ when writing for a specific audience? How might the work of the person contributing graphics differ?

Neil Gaiman, author of the Sandman comics, once said that he would never write a comic without knowing first who his artist would be. He believed that a writer should write to his artist’s strengths. There are many writers who have a very specific target audience in mind when they write, and write specifically for them. When I write Dark Tower stories for the graphic novels, I try to remain true to the characters. As long as I am true to them, then I think that Dark Tower fans will give the comics a sympathetic read. I suppose that when I write, I try to remain true to the characters I’m writing about. I think they know their audience!

When it comes to the art for mainstream graphic fiction, audience does become an important issue to consider. There are fairly strict guidelines governing nudity, violence, and sexuality in comics. (If you are interested in this subject, you might want to read about the history of the Comics Code Authority.) At companies like Marvel, comics for ages 12+ can have mild violence, but no full nudity or overt sexuality. For its more adult comics, Marvel has created the Max line. For years, DC’s more adult comics tended to be published under the Vertigo imprint.

- Have you ever contributed to the adaption of a novel or story into a piece of graphic fiction?

Yes, I’ve done this a lot! I adapted Stephen King’s novels Wizard and Glass, The Gunslinger, The Little Sisters of Eluria (that’s a novella), as well as The Drawing of the Three into graphic novels. I also adapted the King/Straub collaboration The Talisman. In addition, I adapted Sherrilyn Kenyon’s first two Lords of Avalon novels into graphic novel form.

- Do you have a personal favourite graphic novel and why?

My favourite graphic novel series is Sandman, written by Neil Gaiman and published by Vertigo. These stories have a dreamlike vision (not surprising, since Sandman is the lord of sleep and dreams), but are also incredibly literary. The Sandman graphic novels won an Eisner Award, a World Fantasy Award, and a Bram Stoker Award, among others.

- Do you think the genre of picture books, stories told purely in pictures rather than words, relates to the kind of fiction you produce? Why or why not?

Stories told purely in pictures are very different from what I do, but I still love them. Picture books are traditionally considered to belong purely to children’s fiction, but there are many that have been written for adults too. The surrealist artist Max Ernst created stories, novels, and poems completely in images, as did Frans Masereel.

Hope this helps.

Good luck and keep writing!